Eric Gill

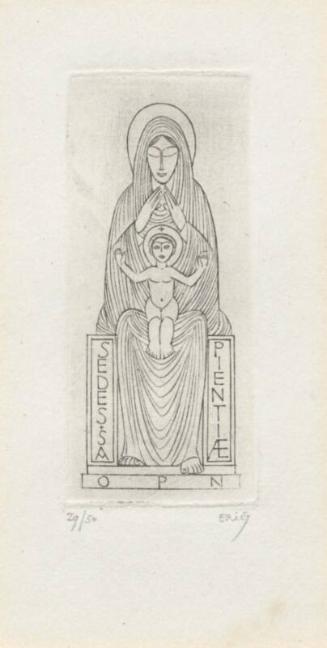

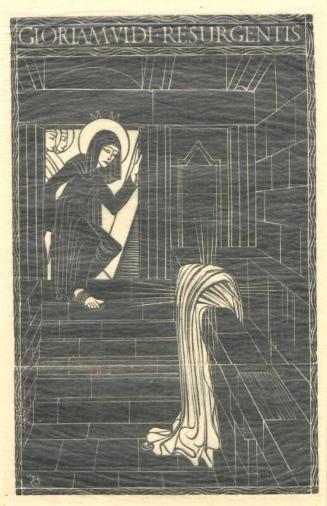

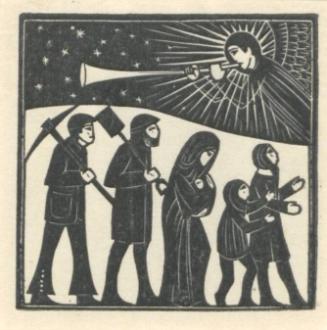

Eric Gill (1882-1940) began his artistic career carving letters on tombstones, but he firmly believed that the ideal craftsman should be able to work in a variety of media and, himself a man of many talents, he soon began to sculpt, do caligraphic work and create woodcuts and wood engravings. From 1906 onwards he produced numerous wood engravings. After some years of jobbing work - designing bookplates and Christmas cards - he began working for the best private presses: Cranach, St Dominics and the Golden Cockerel. Engraving was a skill that he pursued until his death in 1940.

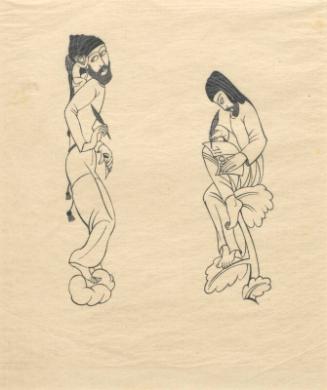

Gill's beliefs were rooted in the Arts & Crafts theories of William Morris and John Ruskin. Like them, he longed for a time when an artisan could paint, sculpt, lay bricks and cobble boots. Art he always insisted, should be useful not just decorative. Towards the end of the 1907, in an attempt to realise his dreams of an idyllic working community, he and wife and daughter moved to Ditchling in East Sussex. There they set up a commune where Gill worked as a stone carver and sculptor and the women of the community attended to household and farming chores.

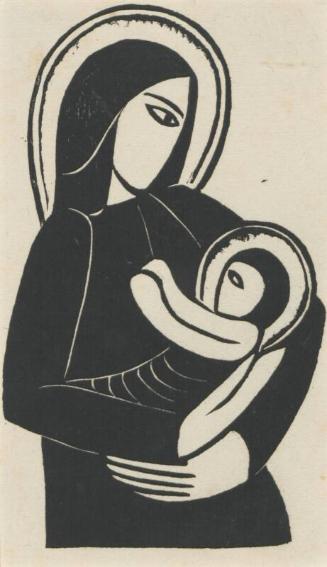

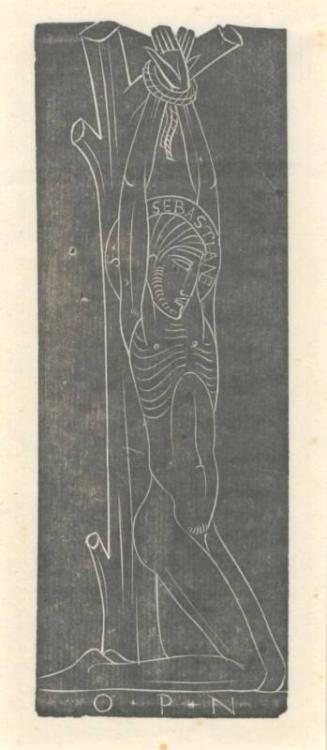

Gill was deeply religious and he and his wife became novices in the third order of St Dominic. This order frowned on frivolous dress. Gill's own preference for the puritanical dress of artisan's working clothes, such as smocks and simple head cover, is illustrated in his Self Portrait in profile. Gill believed that the Catholic faith had abolished the opposition between flesh and the spirit and in his religious art he endeavoured to interpret this aspect of his religion. There was, however, a strange dichotomy in Gill's logic. He felt very strongly that the display of underwear in shop windows should be banned, but also believed in the purity of the human body, and enjoyed playing tennis in the nude.

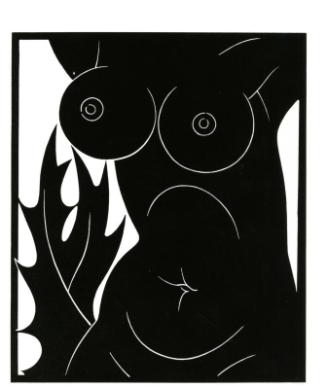

This unique and strange mixture of puritanism and prurience affected many aspects of his art which is, at once, both deeply religious and overtly erotic. His crucified christs, for example, were often naked and unmistakably masculine and caused consternation in many quarters. His woodcut of Eve has a strong sexual element, the snake being distinctly phallic and predatory. Gill's secular work proved to be almost as controversial. His famous sculpture of Ariel on broadcasting House in London shocked the governors of the BBC, who found the male figure far too explicit. Believing his masculine form to be exaggerated they ordered Gill to "cut him down to size".

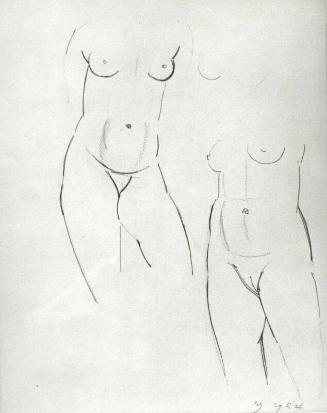

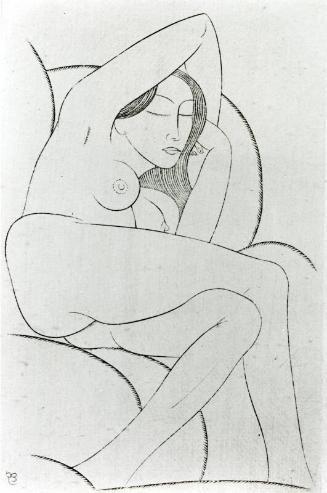

Gill did not start life study until he was forty but was clearly fascinated by the human form. Using clean, hard outlines he idealised the body, often ignoring all investigations of the psyche, any facial expression or features of his model.

The publicist and publisher Douglas Pepler, on observing Gill at work, noted his attention to detail and precision, writing:

The first thing that struck me as an observer of Gill at work was the sureness and steadiness of his hand in minute detail: the assurance and swiftness of a sweep line is one thing (and here he was a past master) but the hairs on an eyelash another - and he liked to play about with the hairs and rays which can hardly be distinguished with a magnifying glass (and easily tended to be filled in with ink in printing)

During the early 1920s Gill created a series of dramatic portraits in profile, illustrated here by Zenia, Thomas and Ruth Lowinsky. They recall early Renaissance portraits - which were often also in profile - but in the way that Gill has printed these wood engravings, with the black ink covering the face rather than sitting in the carved lines of the prints, also suggest at his interest in early 19th century silhouette portraits.

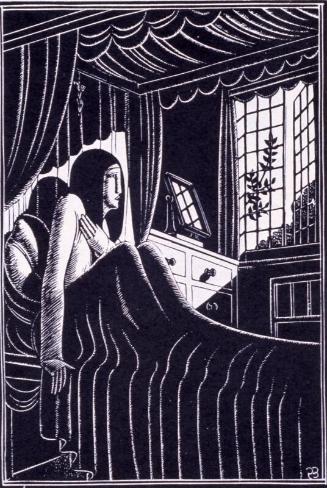

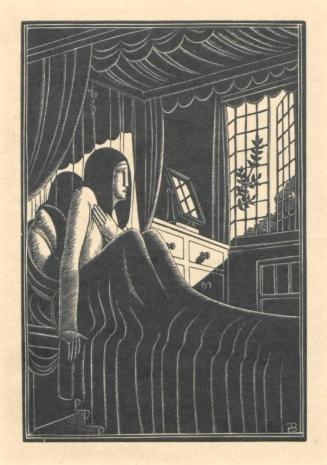

In 1924 financial adversity forced the community to move to a bleaker site, Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains. Gill ended his publishing relationship with Douglas Pender at about this time and began to work with Robert Gibbings who had recently bought the Golden Cockerel Press, which had been founded four years earlier. In spite of his harsh surroundings it was during his years in Wales that Gill created some of his most memorable and erotic line engravings, such as The Sofa and Girl in Bath I & II, which were based on life drawings that the artist made of his daughter Petra.

Gill's religious, ethical and artistic beliefs set him apart from most of his contemporaries. The value that he placed on hand made goods was sound but his belief that the masses would rise up and reject machine-made goods and like him, demand the right to support themselves by handicraft - proved to be unrealistic. Nevertheless, in living out his artistic dream he came to create things that have quite clearly stood the test of time. His lettering - Gill Sans and the serif faces Joanna and Perpetua, named after his daughters - are still widely in use today. His elegant and forceful sculptures adorn many buildings throughout Britain. Finally his woodcuts and wood engravings which, in spite of their controversial content, reveal Gill's virile imagination, physical expertise and immense talent.