Edward Raban

Aberdeen’s first printer, Edward Raban was of German extraction and raised in the English West Midlands. He fought against the Spanish in Flanders, and gives us some insight into his life in the army in a text that he wrote entitled Raban’s Resolutions against Drunkenness: ‘we made day and night all one with eating, drinking, playing, swearing…He that could not quaff a dozen pots of beer or a bottle of wine, and swear an hour together, he was not fit to go in our company’. Raban was to criticize this lifestyle in his Resolutions, and he was also disparaging about his role in defeating the Spanish: ‘I (alas), for mine own part (unto God’s glory (though my shame) may I say it) have had too great a share in that business’.

Raban’s time in the Netherlands, from 1600 to around 1610, was followed by a period of travel, largely in Germany. He does not seem to have been printing at this stage, but there certainly were printers by the name of Raban, or Raben – possibly Raban’s relatives - in Germany at the time. Indeed, they carried out academic work for Aberdeen and St Andrews, perhaps giving Edward Raban a link with Scotland. He seems to have acquired his printing expertise on the continent a little later though, probably at the Pilgrim Press in Leiden, a controversial press that produced inciteful puritanical books, leading to its closure around 1619. From Leiden, Raban may have brought a trademark set of ornaments and type to Scotland, where his first home was in Edinburgh, on the Cowgate, in a house marked by the sign ‘ABC’. It is not clear when he arrived in Edinburgh, but in 1620, he and his sign moved to St Andrews. It may have been there that he became known to the two men who were to draw him further northwards, to Aberdeen.

The first of these men, Dr Robert Baron, Professor of Divinity at Marischal College, was heavily involved in both university and civic life in Aberdeen. Raban worked for him in 1621 whilst still printing in St Andrews, producing the graduation thesis of Baron who was at the time affiliated to St Salvator’s College in St Andrews; presumably, the quality of Raban’s work led Baron to seek his services as Aberdeen’s printer. The exact nature of Baron’s involvement is unclear, as are the relative degrees of town and university influence in bringing Raban to Aberdeen. We do, though, have much evidence for the role of our second man, Patrick Forbes, the second bishop of Aberdeen to feature prominently in this history of Aberdeen printing.

From the outset, Aberdeen’s printer was responsible to burgh and university: a unique situation in Scotland, and one that was to continue for some time. One of the earliest printing jobs that we know to have been carried out by Edward Raban in Aberdeen is dated to 22 July 1622 and was carried out for the university: a collection of theses for King’s College. From this we may deduce that Raban was established in Aberdeen at that time, although it was not until 20 November of that year that he was officially appointed as printer by the Town Council. The terms of his employment underline his very close association with the burgh. Raban’s salary was set at £40 per year, supplemented by a payment of 8d per quarter from each pupil at the Grammar School: a unique arrangement in Scotland, and a clear indication that education was a major stimulus for the spread of printing to Aberdeen. Raban was to pay £40 annual rent to the Town Council for his business premises: a house above the meal market on the north side of Castlegate. When the house needed repairs ten years later, the council recognised the importance of Raban’s role by paying for the improvements to the building.

The house was let to Raban with the guarantee of a cautioner by the name of David Melvill, a burgess of the town and its only bookseller at the time. Melvill was a close acquaintance of Raban’s: he paid the first year’s rent on the print house, and probably continued to do so until his death in 1643, when he may have given his Broad Street premises to Raban – a property that remained in the hands of the town printers until the mid-eighteenth century. Many books printed by Raban in Aberdeen were produced for the bookseller, Melvill. These were popular works: poetry, a chronicle of the kings of Scotland, various religious volumes including a history of three friars of Berwick and texts on church discipline, and latterly two volumes of classical works by Cicero and Ovid. These would have provided some commercial income for Raban and give some indication of the types of book that were being bought at the time, admittedly only by the literate minority.

It was the university and town, though, that commissioned the bulk of Raban’s work, maintaining a great degree of influence over printing in Aberdeen. While Edinburgh was home to several printers, Raban was employed as the sole town printer, charged with all official work and subject to tight controls. He produced many works as ‘universitatis typographus’ [university printer], mainly theological and philosophical tracts; he printed government documents informing of royal visits, warning of Calvinism, or establishing standard customs and dues for the town’s burgesses; and he produced many works for religious use. Publications – particularly of a religious nature - were subject to increasing scrutiny during Raban’s tenure, following a pattern seen elsewhere. By the later 1630s in England, printers required a licence from the Archbishop of Canterbury or Bishop of London, or from the Chancellor of Oxford or Cambridge. In Aberdeen, it was the university that held sway over what could or could not be printed. Raban did fall foul of these controls, not least in 1640 when, amid enquiries into popery, he was accused by the church’s General Assembly of shortening a prayer in a Psalm Book. He was let off following protests that he had only abbreviated the prayer due to a shortage of paper, but this incident can only have highlighted the close control wielded by Raban’s main employers.

Raban did have some freedom in choosing his publications, and indeed wrote some works himself, giving us just a glimpse into his interests. His poetic contribution to a memorial for Bishop Forbes was probably requested by the university, but his work, The Glorie of Man, consisting in the excellencie and perfection of Woman, seems to have been written of his own volition. Finally, Raban established Aberdeen’s first almanac – an annual publication, describing the seasons of the year and containing various entertainments, which was to become the Aberdeen printers’ most prized output, although not until some years after Raban’s tenure.

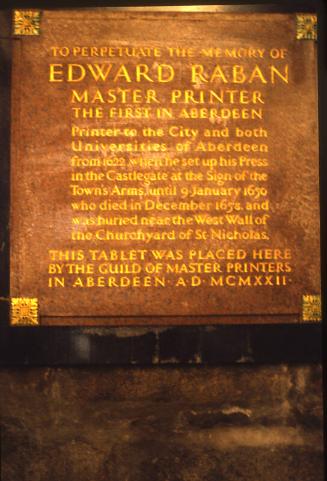

Away from his well-regarded professional life, we have little evidence of Raban. He was married twice, in 1627 to Jeanett Jhonstoun and then later to Janet Ailhous. It was with this second wife that Raban was arrested for brawling with another couple and ordered to pay a fine or face imprisonment. He seems to have faced further legal and financial problems in 1641 when it was demanded that he pay £60 to a certain Thomas Gray, for paper. It is not clear why Raban left his office in 1649, although his publishing had slowed down considerably during the preceding decade. He died in 1658, his importance to Aberdeen recognised by his burial at the west wall of St Nicholas’ Churchyard; two plaques at the church today commemorate Aberdeen’s first printer.