Gallery 18 - People & Portraits

People and Portraits

Throughout history portraits have been symbols of ancestry, reminders of dynasties and tools of propaganda. But why are the British in particular so obsessed with portraits?

One reason was the rejection of religious images during the Reformation. The rise of puritanism also made classical themes morally suspect. A preoccupation with ancestry and class must also pay a part.

In the 20th century these motivations were shaken by the impact of two World Wars and the advent of new technology. With the increased accessibility of photography, the portrait moved from the formality of a studio setting to a spontaneous image available to everyone.

Today, in the modern digital age, the tradition of the portrait has been shattered and reformed.

Rise of the Portrait

Traditionally portraits were a statement of class and status. They resulted from the combined demands of the patron – usually the sitter – and the fashions and conventions of society.

Early portraiture was preoccupied with the sitter as a symbol: soldier, knight, cleric, or lady of rank. The portrait illustrated the fashionable ideal of the time by flattering the sitter. The setting or surroundings like landscape, sport, animals and possessions often defined the sitter’s social status.

In the more enlightened era of the mid 1700s to early 1800s there was a shift away from this position. Joshua Reynolds, Allan Ramsay, William Hogarth and Henry Raeburn produced portraiture with an increased focus of the personality of the individual.

Models and Muses

The cult of female beauty, particularly beloved by Victorian artists, led to a blurring of lines between portraiture and pictures of mythological, exotic or literary figures.

These pictures are not portraits in the conventional sense, but are something more elusive. The muse inspired a mysterious world of the imagination.

The Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti became obsessed with Jane Morris, the wife of his friend William Morris. With her dark, beguiling beauty, Jane was Rossetti’s muse. He portrayed her often as an unhappy, literary heroine.

In William Dyce’s Beatrice, the fascination with the model was on the part of the patron, Prime Minister William Gladstone. In the portrait the model – a ‘fallen woman’ Gladstone had helped – possesses not only physical loveliness but also a spiritual purity.

‘She is full in the highest degree both of interest and beauty […] Altogether she is no common specimen of womanhood!’ William Gladstone describing Maria Summerhayes, Gladstone Diaries 1825 - 1896

Models and muses

Mariana, a character in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, has been rejected by her fiancé Angelo. Rossetti’s infatuation with his model, Jane Morris, is revealed in the underlying theme of thwarted lovers.

Etty specialised in the nude, leading to accusations of his art being indecent, so in order to sell his works he added elements of mythology or literature. In Somnolency, he crowns his model with poppies symbolising slumber.

Beatrice, the heroine of the epic Medieval poem The Divine Comedy is modelled by Maria Summerhayes, a ‘fallen woman’. Prime Minister Gladstone had ‘rescued’ her, became infatuated with her and commissioned this work.

The features of the figure in The Winged and Poppied Sleep – the long neck and cupid’s bow mouth – resemble those of Mariana, revealing a devotion to the cult of beauty which Solomon shared with fellow Pre-Raphaelites like Rossetti.

Rather than representing specific people, Phillip’s and O’Neil’s paintings of unnamed sitters show the artists’ fascination with the exotic. In Una Maja Bonita, the upright pose and coquettish glance suggest a fiery Spanish temperament.

O’Neil drapes his model in lavish silks and jewellery to convey the glamour that Victorians associated with the ‘Orient’. Like many Orientalist painters, however, he probably used an English model, rather than an authentic Eastern Lady. The model for Eastern Lady also appears in O’Neil’s 1854 painting of Catherine of Aragon.

Through the Looking Glass

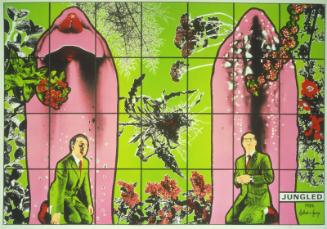

In the early 1900s innovative, modern artists made experimental portraits using loose brushwork and unusual colour schemes.

Following the First World War, the collapse of the aristocracy and huge social change led to the decline of the traditional portrait. However, from the mid-20th century portraiture became popular again. There was a focus on character as never before, with a new informality of presentation.

The conventional portrait was completely overthrown by Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach in favour of a personal artistic statement. Photography made portraiture available to sitters from all kinds of backgrounds and can present a more honest view of them and their world.

These new approaches were in direct opposition to the older ideas of portraits as self-promotion.

Capturing Childhood

During the late 1700s, extraordinary social change led to a new attitude towards children as individuals. Childhood came to be valued as a discrete phase of life and the child portrait emerged as a distinct art form.

Child portraits could be remarkably candid and genuinely moving. But their purpose was also to record a transient moment in times of high mortality. The wealthy wished to capture the image of beloved children and heirs when childhood was short and survival uncertain.

During the 20th century portraits became more informal. Modern artists like James Cowie and Joan Eardley were not commissioned to portray the children of affluent families, but instead found painting ordinary children to be a rich source of inspiration. Full of life, intensity and character, the portraits of these children are often poignant, but never sentimental.

Carte de visite

The carte de visite, or photographic visiting card, was the first type of photograph to be mass produced. Their small size allowed the photographer to take up to eight images on a single plate. The images were pasted onto larger mount cards that had the photographer’s details on them. As the process was relatively inexpensive, it allowed many more people to own portraits of themselves and family members.

Portraits in your pocket

The most important portrait that people encounter every day is on the money they carry with them. These small-scale portraits are not just an image of a person. They symbolise the monarch and state, their self-image and the ideas that they wish to project to the world.

Photographs

Children’s formal portraits are often captured as part of the school year. Many of us recognise the well-scrubbed faces and neat clothes expected on the day of the school photograph.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the phot-booth, originally intended for the easy production of passport photographs, became a plaything.

The informal, uncontrolled, inexpensive and immediate images taken in these phot-booths are also replicated in Polaroid and Instax photographs when there was only really one chance to capture an image.

Selfies, where the photographer controls which image to select and post, are far less spontaneous.

Miniatures

Painted as portable portraits, miniatures were usually of loved ones or given as keepsakes to offer a reminder of the absent person.

Four of the 15 children born to King George III and Queen Charlotte were painted in delicate watercolour on ivory in 1807 by Aberdeen-born Andrew Robertson.

Robertson has depicted keen amateur artist Princess August with paintbrush in hand. These affectionate portraits often belie unhappy circumstances. Sophia revelled against the expectation that she live as a companion to her mother, the Queen, and had an affair with her father’s chief equerry. In 1800 she gave birth to an illegitimate son, Thomas Garth (1800 – 1875), who was brought up by his father in Dorset.

Passions and Possessions

Throughout the centuries portraits have been used for many purposes, but all have a message or meaning.

Decorative figures based on famous and notorious people were popular and affordable items in the 1800s.

Portrait miniatures enable their owners to retain the image of loved ones wherever they go. These portable portraits reflect the sentimental, and sometimes scandalous, relationships between sitter and owner.

‘The reason some portraits don’t look true to life is that some people make no effort to resemble their pictures.’ Salvador Dali

Coins depicting heads of state reflect the power these figures wield over everyday life, and act as a reminder that we are their subjects.

With the birth of photography, possession of a person’s likeness was available to many more. Photographs allow us to create and share someone’s likeness easily, quickly and cheaply – from holiday snaps to selfies.

![Untitled [Unstrung Forms Series] by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham](/internal/media/dispatcher/54999/thumbnail)