GRANITE CITY

Shipbuildervessel built by

Walter Hood & Co.

(Shipbuilder, Footdee, Aberdeen 1839 - 1881)

Date1853

Object NameCLIPPER

MediumWOOD

ClassificationsShip

Dimensionslength 169 5/12' x breadth 28 9/12' x depth 20 1/3'

Registered Tonnage: 772 tons

Registered Tonnage: 772 tons

Object numberABDSHIP000338

Keywords

Official number: 23149

Fate: Abandoned in the Bristol Channel after a storm and subsequent leak in November 1881. Full Board of Trade investigation report is attached below.

Propulsion: Sail

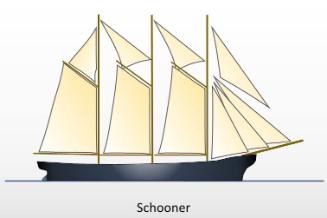

Description: Ship rigged clipper, 1-and-a-half poop and forecastle decks; 3 masts; female figurehead. .

Owners:

11/02/1853: Registered at Aberdeen for subscribing owners;

Henry Adamson, shipowner, 38 shares; William Leask, shipmaster, 12 shares; George Milne of Kinaldie, Aberdeenshire, 8 shares.

Other Owners: James Saunders, Royal Navy, London, 4 shares; John Saunders Jr., banker, Cephalonia, Ionian Islands, 2 shares.

(Aberdeen Register of Shipping (Aberdeen City Archives))

1870: Bilbrough & Co., registered at London

Masters:

1853-63: Master William Leask.

1863-64: Master J. Hodge

1869-70: Master D. Leslie

1870-78: Master R. Ellis

1880-81: Master T. Phillips

Voyages (Lloyd's Register):

1853-56: Aberdeen - China

1858: London - Sydney

1863-64: London - Australia

1965-68: Aberdeen - Australia

1869-70: London - Sydney

1873-74: Cardiff - S. America

General History:

07/03/1861:

Sydney Shipping - GRANITE CITY ship, Leask, from London with 11 passengers (cabin).

(Moreton Bay Courier)

21/03/1863:

(Copying Aberdeen Press) - Aberdonian drowned at sea. John Leask, younger son of Captain William Leask, an experienced seaman belonging to this port, now in command of ship 'STAR OF CHINA' [formerly Master and port owner of 'GRANITE CITY']. John Leask was a fine high-spirited youth about 19 years with that indomitable determination for the sea which only the genuine sailor feels. He sailed about 6 months ago on 'GRANITE CITY', bound for Sydney, on his first voyage. He was washed overboard and lost off Cape of Good Hope.

(Dundee Courier)

14/12/1863:

The new tax on timber: yesterday an extraordinary demand was made on the ship GRANITE CITY. This vessel arrived Brisbane from London 3rd inst. Captain Hodge, however, having been informed that the law would not allow him to break bulk for 20 days, wished to find employment for his crew and, having sprung the fort of sail yard on the way out, and there being a spare one aboard, he determined to have it refitted. On taking steps to land the spar, the landing waiter objected to allow it to be placed on this wharf or even to pass over the ship's side into the water so that it could be towed to the shipbuilder's yard, a short distance away, until the new impost was paid [about £14]. The Captain appealed [unsuccessfully].

(Brisbane Courier)

01/02/1868:

Full rigged ship "GRANITE CITY" of Aberdeen, Watson Master, was being towed (in ballast) from Leith to Shields by steam tug PEARL, south of Farne Islands because of gale ship was cast adrift and anxiety is felt for her safety.

(Bristol Mercury)

[Aberdeen Journal 26/02/1868 reported her on voyage Shields - Singapore being spoken off Dartmouth 17 Feb].

06/10/1869:

Report of ship "GRANITE CITY" of Aberdeen by Capt. Leslie - "Left Sydney Heads 21 June for London; 28th passed Auckland Isles; experienced between New Zealand and Cape Horn strong SE gales and much wet and stormy weather; 9 August Lat 60S, Long 49W passed through large quantity of loose ice, weather thick and foggy, 4p.m. passed a very large iceberg; 13 Aug. experienced a most terrific SW gale, part of bulwarks washed away; 30 Aug. crossed Equator in Long 27W and carried SE trades to 10N and SW winds to 17N".

(Aberdeen Journal)

12/03/1879:

February 26 - the ship "GRANITE CITY" at Delaware Breakwater from Belfast reports having been struck by lightening Jan. 2. She also lost and split sails.

(Freeman's Journal & Daily Advertiser)

07/12/1881:

Capt. Davies and 14 hands belonging to the ship "GRANITE CITY" of London landed at Cardiff yesterday, having abandoned their ship at sea.

(Aberdeen Weekly Journal)

Abandoned off Bristol Channel / December 1881.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Unique ID: 14775

Description: Board of Trade Wreck Report for 'Granite City', 1882

Creator: Board of Trade

Date: 1882

Copyright: Out of copyright

Partner: SCC Libraries

Partner ID: Unknown

Transcription

(No. 1218.)

"GRANITE CITY."

The Merchant Shipping Acts, 1854 to 1876.

IN the matter of the formal Investigation held at Westminster on the 3rd and 4th of January 1882, before H. C. ROTHERY, Esquire, Wreck Commissioner, assisted by Captain BEASLEY and Captain RONALDSON as Assessors, into the circumstances attending the abandonment of the British sailing ship "GRANITE CITY," of London, on the 22nd of November last, whilst on her voyage from Dalhousie in New Brunswick to London.

Report of Court.

The Court, having carefully inquired into the circumstances of the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds, for the reasons annexed, that the loss of the said vessel "Granite City" was due to the violent gales which she encountered in the Atlantic, and which, owing partly to her age, partly to the weight of cargo which she had on board, she was not able to resist, and that the master and crew did all in their power to save her, and that they were justified in abandoning her when they did.

The Court is not asked to make any order as to costs.

Dated this 4th day of January 1882.

(Signed)

H. C. ROTHERT, Wreck Commissioner.

We concur in the above report.

(Signed)

THOS. BEASLEY,

Assessors.

A. RONALDSON,

Annex to the Report.

This case was heard at Westminster on the 3rd and 4th of January instant, when Mr. Middleton appeared for the Board of Trade. The owners and the master of the "Granite City" were present, but were not represented by either counsel or solicitor. Eight witnesses having been produced by the Board of Trade and examined, Mr. Middleton handed in a statement of the questions on which the Board of Trade desired the opinion of the Court. The managing owner of the "Granite City" having recalled the master, then addressed the Court on behalf of himself and his co-owner, and Mr. Middleton having been heard in reply, the Court proceeded to give judgment on the questions on which its opinion had been asked. The facts of the case, so far as they are undisputed, are as follow:"

The "Granite City," which was a wooden barque, belonging to the Port of London, of 771 tons gross and 726 tons net, was built at Aberdeen in the year 1853, and at the time of her loss was the property of Mr. Joseph Parson and of Mr. Robert Alexander Stewart, of No. 3, Fen Court, in the City of London, Mr. Stewart being the managing owner. She left Dalhousie in New Brunswick on Saturday the 12th November last, bound to London, with a crew of 14 hands all told, and a cargo of 300 to 310 standards of deals, including the deck load. The crew at first would not do any work, but on the master refusing to give them anything to eat unless they did so, they on the following day returned to their duty under circumstances which we shall presently have to detail at length. For the first few days they had moderate breezes from the N.W., but on the 15th the wind began to freshen, and on the 16th it blew a hard gale varying from S.W. to N.W. During that night the vessel laboured a good deal, and on finding on the following morning that the deck load had started, the master deemed it prudent to jettison it, and on this being done the vessel rode more easily. On the same day the standard of the windmill pump broke, and they had to work the deck pumps, but on the windmill pump being repaired it was found sufficient to keep the vessel free. On the 18th the gale moderated, but on the 19th it began to blow again, and the vessel was accordingly hove to on the starboard tack. During that day the lower main topsail was blown away, and on the following morning, it being found that four of the stanchions on the port and two on the starboard side had started, and that the oakum had worked out, the master stopped up the holes with oakum, and the weather having moderated they bent a new lower main topsail. At about 8 o'clock the same evening the gale recommenced, and at 2 of the following morning the lower main topsail blew away again. Between 5 and 6, the captain observing that the vessel was dipping her port quarter very heavily, and that she seemed to be very stagnant in the water, ordered the second mate to sound the well, and on his doing so it was found that there were 16 feet of water in the hold. All hands were accordingly called to man the pumps, but as the sea was making a clean breach over her, it was found impossible to stand to them. Accordingly the captain, feeling certain that the vessel would be soon water-logged, ordered water and provisions to be carried up into the main and mizen tops; and at about 8.30, the cabin beginning to be flooded, they all took to the rigging. After a time some wreckage was observed to be coming from under the port quarter, and shortly afterwards the decks began to lift, upon which the master, fearing that the ship was breaking up under them, ordered the boats to be got ready. During the night the wind and sea moderated, and they were able to remain on the fore part of the deck. The next morning, however, it was observed that the port side of the vessel from the main rigging aft had come away both planks and timbers as low down as the main deck, and that it was trailing alongside; and the sail of a vessel, which proved to be the "David Taylor," having shortly afterwards hove in sight, all hands got into the lifeboat, and having pulled towards her, they were taken on board, and were brought safely to and landed in this country. We are told that when the vessel was abandoned she was in about latitude 44° 39' north, and about longitude 38§ west, or about 300 miles to the east of Newfoundland; and there can be little doubt that she has long since foundered.

Now the first question upon which our opinion has been asked is, "Whether, when the "Granite City" left Dalhousie on the 12th of November last, she was in good and seaworthy condition?" This, as Mr. Middleton truly observed, is perhaps the most important question in this inquiry; and before answering it, it may be well to give a brief history of the vessel. She was, as I have already said, built at Aberdeen in the year 1853, and was originally classed A 1 at Lloyd's for 10 years; whether on the expiration of that time her class was renewed we are not told, but in 1870 she was restored to her original class for 7 years, and on the expiration of that time she was continued in the same class for 5 years more, which would bring her down to 1882. In April of last year Mr. Parson, who had owned 16/64th parts of her since 1874 or 1875, purchased in addition 20 shares, thus increasing his interest to 36/64th parts, the remaining 28/64th parts being at the same time bought by Mr. Stewart. Having done some repairs to her at Cardiff, the owners then sent her to St. John's, New Brunswick, where Mr. Stewart has a branch house, and where she was thoroughly repaired at an expense of 833l.; and having then been surveyed by Lloyd's surveyor at that place, she was reported fit to be continued in the first class. On the completion of the repairs the vessel took in a cargo of deals, with which she sailed for Faversham, and having there discharged her cargo returned in ballast to Dalhousie, where she took in the cargo with which she sailed on her last voyage. It seems that the crew who had brought the vessel to Faversham had been engaged at St. John's for the voyage to this country and back again to New Brunswick; accordingly, on the vessel's arrival at Dalhousie, all, with the exception of two men who had been shipped in England, left her, and it became necessary to hire a fresh crew. Eight new hands were accordingly engaged at St. John's, and were sent by rail in two batches to join the ship at Dalhousie. The first batch, which consisted of 5 men, joined her on the 6th or 7th, the other three on the 11th, the day before she sailed, and of these three have been produced before us, one belonging to the first and two to the second batch it would seem that as soon as the men saw the vessel they took a dislike to her, and determined not to go in her; they were not able to specify any defect which would render her unseaworthy, but they said that she looked old, and that they thought that she would not carry them safely across the Atlantic. The men were to have had thirty dollars each for the run to this country, and of this the first batch had had twenty dollars each advanced to them, and the second batch fifteen, all of which had actually gone to the boarding-house keepers. Under these circumstances the master was very unwilling to let them go ashore, fearing to lose them, but he told them that he was willing to have a survey on the ship; this, however, the men declined, saying that they wanted to be taken before a magistrate. On the 11th the master brought three surveyors on board, namely, a shipbuilder, the port warden, and a pilot, and these gentlemen having reported that the vessel was not making any water to speak of, and that she was "a " good and substantial vessel in every way, and " adapted for the trade" in which she was engaged, the master determined to sail whether the men liked it or not. Accordingly early on the morning of the 12th a gang of men came on board and got the anchor up and the vessel under weigh, and she proceeded to sea, the 8 hands refusing to lend a hand. The men still refusing to do duty, the master told them that he should not give them any food, and at length on the following day, being starved out, they went to work again. I have said that the men were not able to specify anything which would be likely to make the vessel unseaworthy; they complained indeed that the forecastle was too small for ten men, upon which the captain told them that he would berth two of them in the carpenter's shop; they also said that there was no stove in the forecastle; but neither of these things would render the vessel unseaworthy. Flannigan indeed, one of the men, stated that the decks were not in good condition; but in this he was not supported by the others. They admitted that the sails and rigging and pumps were good, and all that they could say against her was that she was old, that they did not like her, and that they did not think she would carry them safely across the Atlantic. On the other hand the master, who had been in her since she had been bought by her late owners in April last, and who had made the voyage from Cardiff to St. John's, thence with a cargo to Faversham, and back again to Dalhousie, as well as the chief officer who had joined her at Faversham, stated that, although old, she was in their opinion a good vessel, and they shewed their confidence in her seaworthiness by going in her even with a very unwilling crew. We were told also by Mr. Parson, who had acted as broker for the vessel since 1870, that up to the last year she had been regularly engaged in the East India trade, bringing rice and cotton from Madras and sugar from Java, and that since he has had a share in her they had never made a claim on the underwriters. He told us also that they had spent in repairs upon her 445l. at Belfast in April 1878; 500l. in caulking and remetalling her at New York in 1879; 163l. at Greenock in May 1880; 111l. at Cardiff in 1881, besides the 833l. spent upon her in June and July last at St. John's, New Brunswick. Taking all these circumstances into consideration, the fact that such large sums had been spent upon her within the last few years, that only in July last she had been apparently opened up, and put into a thorough state of repair at a very large expense, that she had been so recently surveyed by Lloyd's surveyors, and was in the first class at Lloyd's, and that she had until the last year carried dry and valuable cargoes from the East Indies without damage, and without any claim upon the underwritersâ€"taking all these circumstances into consideration we should have been disposed to think that the men must have been mistaken as to her being unseaworthy, were it not for what subsequently occurred, and for the way she seems to have broken up under their feet. It appears to the assessors that if she had been in a good and seaworthy condition when she left Dalhousie, she would not have broken up as she did, and that there must have been some radical defects, which were not apparent to the surveyors, and which rendered her unfit to encounter the gales which might naturally be expected at that season of the year in crossing the Atlantic, and which a good seaworthy ship would have been able to resist. We are therefore not prepared to say that, when she left Dalhousie on the 12th of November last, she was in a thoroughly good and seaworthy condition.

The next question upon which our opinion is asked is, "What freeboard had she, and was such freeboard sufficient?" On this point the evidence is, perhaps, not very satisfactory; according to the master and chief officer the Plimsoll mark when they left Dalhousie was very near awash, and that to the best of their belief would give her a freeboard of about 4 feet or 4 feet 6 inches. Now a freeboard of 54 inches on a depth of hold of 20.2 feet would give less than 2 3/4 inches to every foot depth of hold, which the assessors think would hardly be sufficient for a vessel of her age crossing the Atlantic at that season of the year. They think that 300 to 310 standards of deals, which it seems she had on board, was a very heavy cargo for her, and that under the circumstances she should not have had less than three inches of freeboard to every foot depth of hold.

The third question upon which our opinion has been asked is, "Whether the load-line was obliterated?" According to the mater the Plimsoll mark was quite distinct when the vessel left Dalhousie; he told us that there was a copper disc on the vessel's side to indicate the position of the Plimsoll mark, and that it had been painted white when the repairs were being done in June or July of last year. He admitted, however, that on the last voyage out they had black varnished the top sides, and that the tar might have run down over the disc; and, if so, it is quite possible that the rafts and lighters which came alongside might by rubbing against it have spread it over the plate and so obliterated the mark. The chief mate also said that the Plimsoll mark was visible, but he could not tell us what colour it was; he inclined, however, to think that it was black, and that it had been painted over; but if so, the side of the vessel being black, it would hardly have been visible. The boatswain, or acting second mate, who joined the ship at Dalhousie on the 7th, told us that he did not remember to have seen the Plimsoll mark at all; and the three A.B's also say that they did not see it. On the whole, seeing that one of the first things that a seaman looks for when he joins a ship is the position of the Plimsoll mark, to see if she is more deeply laden than she should be, we are disposed to think that if the mark was not wholly obliterated it was not so distinctly marked on the vessel's sides as the Act seems to require.

The fourth question that we are asked is, "Whether she carried too heavy a deck load, having regard to the structural strength of the vessel?" According to the master she had from 15 to 18 standards of deals on deck. For a good strong vessel that would not be an excessive amount, and, as Mr. Middleton has truly remarked, the deck load had been jettisoned before the vessel sustained any of the injuries which led to her loss. At the same time the assessors are disposed to doubt whether an old vessel like this, 28 years old, ought when crossing the Atlantic to have had any deck load at all at that season of the year.

The fifth question upon which our opinion is asked is, "What was the height of the deck load, and did it exceed 3 feet?" According to the seamen the deck load was from 3 feet to 3 1/2 feet high, but they were not prepared to swear that it was more than 3 feet high. According to the captain, the chief mate, and the boatswain, the after-part extending from the break of the poop to the after-end of the deck house was nine deals high, whilst forward of this they were only six deals high; this would give, assuming the deals to have been 3 inches each, 27 inches for the after-part and 18 inches for the fore-part. As, however, New Brunswick deals are, we are told, ordinarily 3 1/4 to 3 1/2 inches thick, it would make the after-part of the deck load some 30 to 32 inches high, and the fore-part 19 to 20 inches; but there is no evidence to show that at any part it exceeded 3 feet.

The sixth question upon which our opinion is asked is, "Whether the deck load was properly secured?" All the witnesses, except Flannigan, stated that the deck load was properly secured with chains and ropes, but we are not disposed to place any reliance on his evidence, as he was not confirmed on that point by any of the other witnesses. That it subsequently got adrift is no proof that it had not been properly secured, for I am told that this often happens in crossing the Atlantic during tempestuous weather such as that which this vessel encountered.

The seventh question that we are asked is, "Whether the master was justified in taking the protesting seamen to sea against their will?" it is quite clear that the men were unwilling to go to sea in her, and would rather have been sent to prison, and that they asked to be taken before a magistrate. Under these circumstances, and looking at the 243rd section of the Act of 1854 and at the 7th section of the Act of 1871, which prescribes the mode in which a master should act when his crew refuse to go to sea, there can be no doubt whatever that the master was not justified in taking them to sea against their wills, but he should have taken them before a magistrate. At the same time we are ready to admit that great allowance must be made for him, as the winter was coming on and there was a fear of the vessel being frozen in, and in the event of the men being sent to prison by the magistrates there might have been great difficulty in obtaining substitutes for them. On the whole, although the master was not justified in taking them to sea against their wills, we think that great allowances must be made for him.

The eighth question upon which our opinion is asked is, "What was the cause of the vessel making so much water on the morning of the 21st of November?" It would seem from the evidence that the water came in on the port quarter and below the level of the cabin floor. We are told that the vessel had a long projecting counter, and as she rolled this would necessarily strike the water with great force, and the deeper she was the greater would be the force with which it would strike. It seems to the assessors that some of the butts or hood ends may have been started by the repeated blows which she received under the counter, and that thus the water got into the vessel.

The ninth question that we are asked is, "What was the cause of the breaking up of the vessel?" That the decks should have begun to lift when the vessel became waterlogged is perhaps not surprising, but that the side of the vessel from the main rigging aft to the stern post should have opened, not the planks only, but the timbers also being carried away, shews in the opinion of the assessors that there must have been something very faulty in that part. The boatswain on being asked the question saidâ€""I should think that the timbers must " have been old and pretty rotten for the planks to " come away in that way;" and in that opinion the ??ors are disposed to concur. The cause of the vessel breaking up as she did was in their opinion due to her being very old and to the heavy cargo which she had on board, rendering it impossible for her to contend against such weather as she might naturally expect in crossing the Atlantic at that season of the year, and which a stronger vessel would have been able to resist.

The tenth question upon which our opinion is asked is, "Whether all proper efforts were made to save the ship?" In our opinion they were. Nothing that the master and crew could have done could possibly have saved her.

The eleventh question that we are asked is, "Whether the vessel was navigated with proper and seamanlike care?" In our opinion she was. We were told by the chief officer that he had served in her 17 years ago, and that when they got into bad weather the vessel took so much water on deck that they found that they would run her, and that it was necessary to heave her to. In bringing, therefore, the vessel to when the wind and sea became heavy, the master seems to have taken a proper course.

The twelfth question is, "Whether she was prematurely abandoned?" We think not. The vessel was evidently fast breaking up when they took to the lifeboat, and had they remained much longer in her they would probably have gone down with her.

The last question which we are asked is, "Whether the master and officers are or either of them is in default, and whether blame attaches to any other person for the casualty?" And it is added that "the Board of Trade are " of opinion that the certificate of the master should be " dealt with." In having taken the men to sea against their wills, and perhaps also in having put so heavy a cargo in her, well knowing that she was a very old ship, and that they were about to cross the Atlantic in midwinter, when they might reasonably expect to encounter some very severe gales, we think that the master was somewhat to blame. Seeing, however, that this last point has not been very strongly pressed against him by the learned counsel for the Board of Trade, who stated that the application to deal with his certificate was made rather as a matter of form; considering also that the vessel had recently been repaired at a heavy expense, and that she had a first class at Lloyd's; that those facts were well known to the master, and that whatever defects she may have had escaped the observation not only of Lloyd's surveyors, but of the three surveyors called in to inspect her on the day before her departure, we are not disposed to deal with his certificate; nor does it appear to us that any blame attaches to any of the other officers of the vessel. As regards the owners, there is in our opinion nothing to shew that they are in any way to blame for this casualty, for they seem to have done everything in their power to send her to sea in a good and seaworthy condition. I may add that, although Mr. Parson had insured his 36/64th shares of her in the sum of 950l., which we are told was very considerably less than its value, Mr. Stewart, the managing owner, and the owner of the remaining 28/64ths, the owner also of the cargo which she had on board, and which had been sold to arrive for 1,700l., was wholly uninsured. It has been said that this Court has no right to inquire whether an owner's interest is or is not insured, and whether to the full value or not, but I cannot concur in that opinion. It appears to me that if in the course of one of these inquiries it should transpire that the owner had greatly over-insured the value of his interest in the vessel, that fact would no doubt be strongly pressed against him if there was reason to think that she had been wilfully or negligently cast away. On the other hand, if an owner is wholly uninsured, and is a considerable loser by the casualty, it may fairly be taken as some evidence of his bona fides. On the whole there is nothing to show that the owners were in any way to blame for this casualty.

The Court was not asked to make any order as to costs.

(Signed)

H. C. ROTHERT, Wreck Commissioner.

We concur.

(Signed)

THOS. BEASLEY,

Assessors.

A. RONALDSON,

L 367. 988. 150. 1/82. Wt. 203. E. & S.

Note: converted to barque rig 1880?

1841

April 1827

15 February 1858